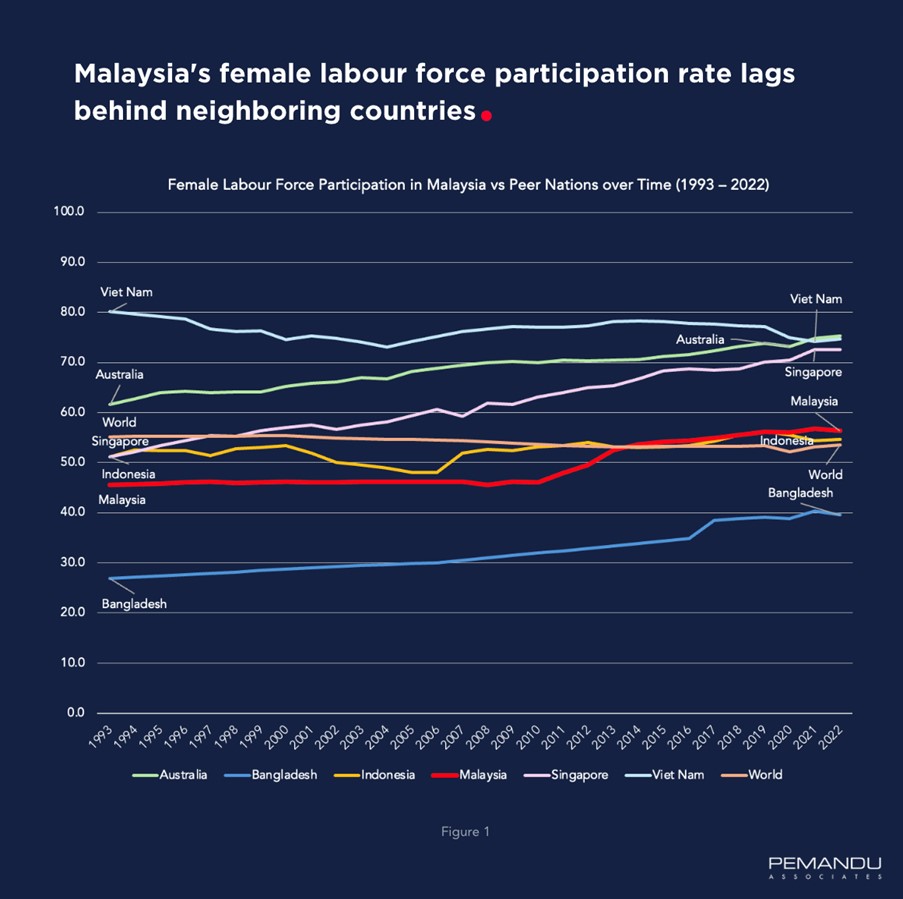

For a mix of sociocultural, political and perhaps economic factors, Malaysia always seems to have struggled with a lower female labour force participation rate than some of our neighbouring countries. Hovering in the mid-50-per cent zone, Malaysia is on a par with Indonesia and the global average, but about twenty percentage points behind Singapore, Vietnam, and Australia (Figure 1). The Malaysian rate also falls short of South Korea and Thailand, who hover in the mid- to late-60 percent zone.

Source: World Bank (data.worldbank.org)

Raising that rate has consistently been a national priority, and Malaysia has undertaken all sorts of initiatives to that end, from return-to-work corporate tax deductions to skilling programs to childcare subsidies and vouchers. As another International Women’s Day rolls around the corner, we take a quick look at how the country has fared in that regard over the last ten years.

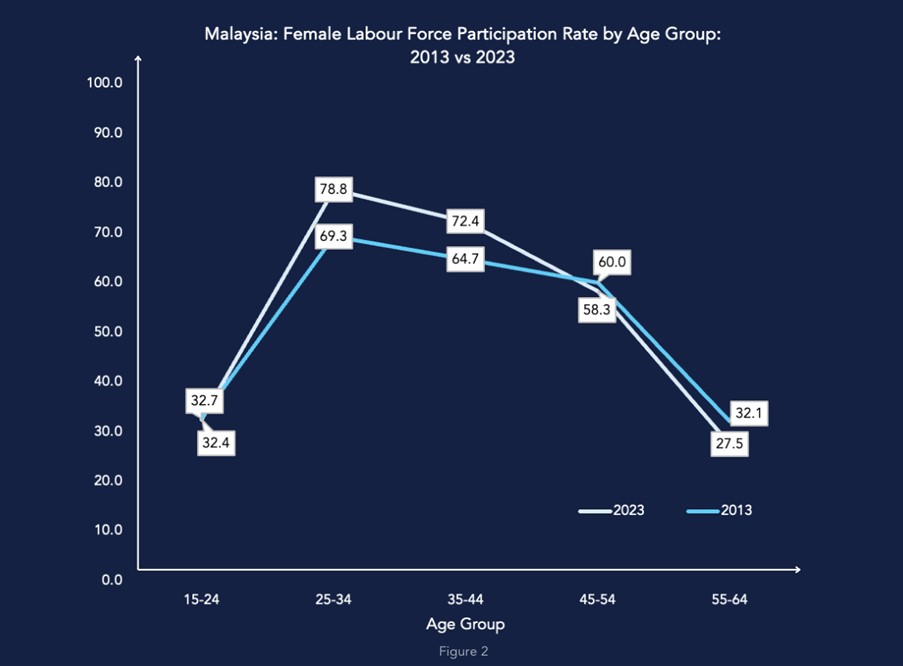

Source: DOSM Labour Market Review Q4-2023; DOSM statistics as cited in KPWKM Perangkaan Wanita Keluarga dan Masyarakat 2014

Clear strides forward in labour force participation

The 2013-2023 decade brought with it a global pandemic, several wars, and other economic shocks. And yet: Malaysian women seem to have still made some gains in terms of their labour market participation rate.

The overall labour force participation rate increased from 52.4% to 56.2% in this ten-year period, and while the gain of 3.8% may seem small, every incremental increase is hard fought. It means an additional 1,358,000 women are participating in the workforce in 2023 as compared to ten years before; the net gain (discounting population growth) is estimated to be circa 440,000 women.

Participation in the youngest age group (15-24 years) seems to have made no gains at all, likely affected disproportionately by the pandemic and related economic effects. In any case, this is a hard group to get a handle on, as it includes a diverse set of youth profiles: out-of-school children, recent graduates, etc. Labour force participation has always been lower in this age group compared to the two groups that come after.

However, in 2023, women aged 25 to 44 years of age saw higher rates of participating in the workforce than in the decade prior. The 2023 25-34 age cohort outdid the previous age cohort by almost 10 percentage points, and the 2023 35-44 age cohort outdid the previous cohort by almost 8 percentage points (Figure 2).

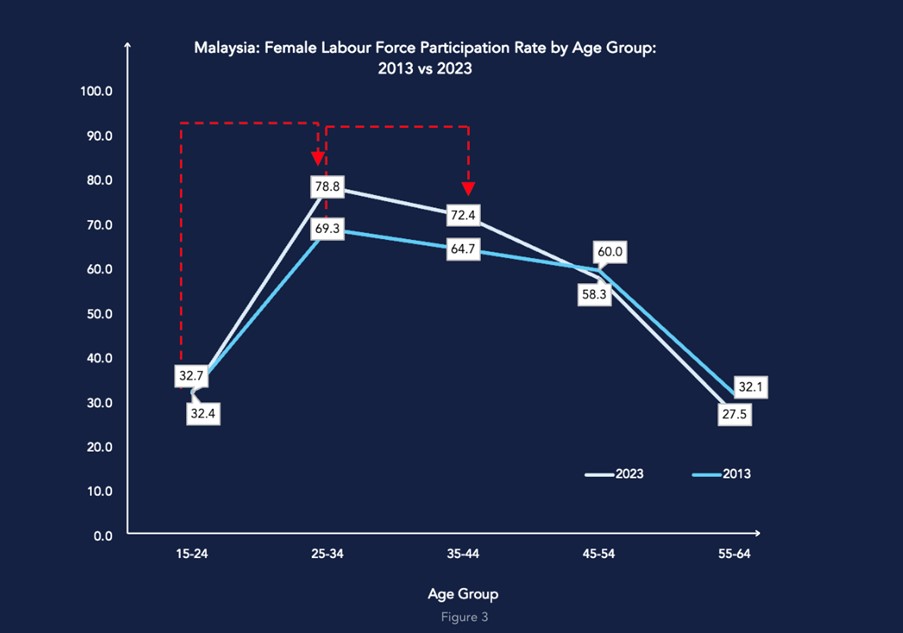

Looking at the data longitudinally (and assuming that the individuals in each age cohort remain roughly the same and disregarding any significant cohort changes as a result of Covid-19), we not only see that subsequent cohorts seem to be making larger gains than the previous, we also see indications of some gains in the same age group over time. For example, the 35–44 age cohort’s labour force participation rate went from 69.3% to 72.4% between 2013 and 2023 (Figure 3). It’s unclear how to interpret that number in the abstract, but perhaps we are seeing that first glimpse of that “second wave” of labour force re-entry, and at the very least, it seems like a sign that this cohort is not going to leave the labour force as rapidly as previous ones.

“Return to Work” remains a challenge

The overall pattern of labour force participation remains the same, with labour participation rising and then falling over the course of the female population’s working years. Our nation continues to be eluded by the second “wave” of labour force participation — the return to work after initial exit during the “child-bearing years” — that is observable in peer nations.

Graphically, this would be typically represented by a rough inverted “W” shape in labour market participation over time, but in Malaysia’s case, we see, at best, an inverted “U,” with the hope of a flattening labour force participation rate for the 35-54 age ranges.

Source: DOSM Labour Market Review Q4-2023; KPWKM Perangkaan Wanita Keluarga dan Masyarakat 2014

May the future hold more choices for Malaysian women

As policy analysts, we are taught to look for broad patterns in data and generalisable, evidence-driven conclusions that can inform next steps. However, having spent a considerable amount of time working in programs and policy initiatives aiming to increase female labour force participation, I cannot help but look at the absolute number of unemployed women in Malaysia at the present moment: ca. 240,000 women. That number, accounting for ~3.5% of the female work force, represents the women who want to work, are looking for work, but are unable to secure employment.

Economically, that’s not a worrying number. It’s not far from the male unemployment rate, and almost exactly what economists would call “optimal.” Within the epistemic limitations of survey data, we can conclude that: the female labour force has grown, there are more women who can and want to work, and almost expectedly, there are more women who do not have jobs.

However, that’s still a quarter of a million women, most likely under 24 years old, and most likely struggling to navigate both the confusing world of job searching as well as cultural and familial pressures in their effort to find a job. My heartfelt hope is that these 240,000 women don’t give up.

The solutions for women who are not actively seeking work are less clear. These women considered “outside the labour force,” consistently cite household/family responsibilities as the cause of their non-participation (regularly 40-60% in each labour force survey). Addressing this issue involves affecting change in our entire approach to the “care economy”, i.e. the way our society organises the (paid and unpaid) care work on which it depends for its very survival.

As we celebrate International Women’s Day, we salute all Malaysian women: those who work, those who don’t, those who made hard choices to be able to work or not to work, and those who never had those choices to begin with.

If the gains we have made on the whole over the past decade are any indication, there is reason for hope that ten years down the line more Malaysian women will be able to make those choices for themselves.