Introduction

Somalia stands at a historic inflection point. Following decades of fragility, scarred by civil war and natural disasters, the country is beginning to shape its own path towards renewal. The launch of Somalia’s Centennial Vision 2060 marked an ambitious aspiration: to reimagine and rebuild a resilient, inclusive, and self-reliant state. At the heart of this vision lies the National Transformation Plan (NTP I), a five-year roadmap that chart out the nation’s first steps towards this future.

While not without its imperfections, the NTP represents a profound shift. For the first time, national planning has been led from within. Ministries, agencies, member states, local associations, and even private sector players were brought into a joint process of reflection and design. With PEMANDU’s facilitation, its signature 8-Step Big Fast Results Lab process enabled government institutions to go beyond mere rhetoric, developing detailed implementation plans, activity-based budgets, and measurable KPIs in tandem with local stakeholders and grounded in local realities. Unlike in previous iterations, national strategies had been largely donor-authored and externally driven. The NTP however represents a statement of reinvigorated statement of intent, signalling Somalia ambition to reclaim agency and ownership over their own development agenda and vision.

With the NTP being Somali-owned and Somali-led, the document has already served as a rallying point for reform across government and society, spurring conversations, and breaking ground for a stronger, more responsive state. At a period of heightened geopolitical instability and uncertainty and the withdrawal of major donors such as USAID, the urgency for self-determination becomes ever more pertinent.

From Dependency to Ownership: Somalia’s NTP Signals a Break from the Past

The NTP marks a critical departure from Somalia’s approach to development. Serving as a launchpad for the Centennial Vision 2060, it lays out a five-year pathway towards inclusive growth, institutional resilience and social development. The plan reflects a purposeful shift in approach and execution, introducing a more deliberate and inclusive way of shaping national development. It is delivery-focussed, prioritising implementation over rhetoric and centrally coordinated through the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), a clear institutional anchor for implementation and accountability.

A distinctive feature of the plan’s design is the way it brings together both top-down leadership and bottom-up participation. Early alignment and buy in was secured at the political level through Cabinet Workshops and consultations involving ministers and senior officials. This consorted effort laid the foundation towards the need for a national level implementation.

What followed was a nationwide effort to translate that mandate into action. Through a series of sectoral Labs facilitated by PEMANDU, Ministries, agencies, Federal Member States, private sector actors and civil society organisations were brought in under one roof. These Labs were not passive consultations; they were designed to be intensive, outcome-oriented sessions that demanded real-time decision-making, prioritisation, and ownership. By collapsing the usual silos and bridging the gap with non-state stakeholders, issues that would typically be mired in bureaucratic delays were surfaced and resolved on the spot. Whether dealing with regulatory hurdles, coordination breakdowns, or overlapping mandates, issues that would typically stall within bureaucratic processes were addressed directly and resolved in situ.

The result was not a plan built in isolation, but one shaped by those responsible for delivery. Sector teams developed implementation roadmaps, activity-based budgets, and measurable KPIs—many seen for the first time. The process was exacting, but it generated shared accountability and forward momentum. What emerged was more than a vision, it was a practical framework rooted in institutional realities and owned by Somali leaders committed to seeing it through.

From Fragility to Focus: Translating Challenges into a Development Agenda

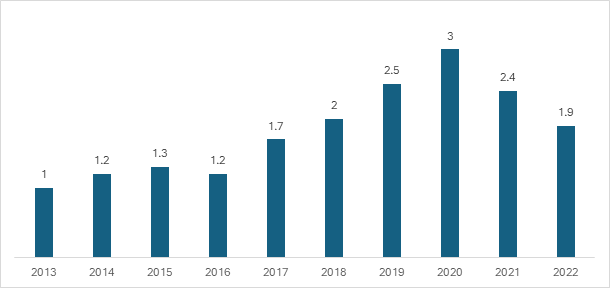

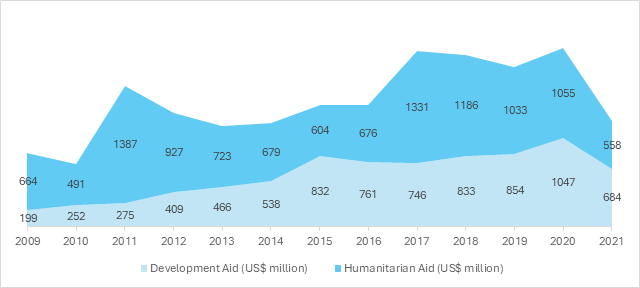

In order to understand the vital need for an outcome-based national transformation plan, it is key to contextualise the nations fragile journey out of the shadows of war. Piecing itself back together after years of disintegration, Somalia’s development landscape has been largely defined by layered and persistent challenges. Years of conflict have weakened institutions and degraded infrastructure. Public services are limited, and much of the economy operates informally. These vulnerabilities are intensified by recurring climate shocks and shifting geopolitical dynamics. The recent withdrawal of large-scale donor assistance, including from long-standing partners such as USAID, has only sharpened the imperative for Somalia to build resilience and reduce dependency.

Rather than sidestepping these constraints and realities, the NTP confronts them directly. It lays out a structured framework to transform systemic weaknesses into opportunities for reform. Investments prioritise initiatives that build systemic resilience, be it through improving institutional capacity, enabling infrastructure or better-targeted social services. Crucially, the Plan also recognises the importance of non-state actors. It highlights high-potential sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, renewable energy, and logistics where private enterprise can drive inclusive growth, generate employment, and reduce regional disparities.

Through the NTP, Somalia begins to move from fragmented responses to a coordinated agenda for development. Ministries are now tasked with leading implementation, but with clearer direction, defined priorities, and a delivery framework that links policy to action. For the private sector and development partners, this clarity is crucial. It offers greater visibility on where support is needed and what outcomes are expected. For Somalia, this represents a shift from reactive and donor-dependent, to proactive and partnership-oriented. In a context of limited fiscal space and elevated risk, the NTP reframes fragility as a foundation for structured, results-driven ambition.

Catalysing Reform Through Private Sector Led Participation and Effective Delivery

The private sector has long sustained Somalia’s economy in the absence of a fully functioning government. In the absence of strong state structures, Somali businesses filled critical service gaps, driven innovation, and sustained economic activity even in the most fragile settings. In many ways, this informal institutional environment has demonstrated the remarkable resilience and merit of Somali enterprises and businesses. Yet it has also exposed the limits of operating without regulated institutional support, particularly as the country begins to transition towards a more formalised and coordinated model of development.

The NTP reframes the role of the private sector as a core partner in Somalia’s economic transformation. Rather than viewing business as a peripheral actor, the Plan positions it at the heart of national progress. In critical growth areas such as energy, agriculture, fisheries, and logistics, the NTP provides clear visibility into sectoral priorities. It identifies investment needs, addresses longstanding regulatory bottlenecks, and lays out a roadmap for targeted reforms that can unlock value. The state no longer sees itself as the sole provider of goods and services. Instead, it is repositioning itself as an enabler; committed to reducing friction, accelerating decision-making, and removing barriers that delay private-led execution.

This shift sends a clear signal that Somalia is ready to create a business environment that is not only open to investment but built for speed and responsiveness. To operationalise this vision, practical mechanisms are already being introduced. Private actors can now submit project proposals directly linked to NTP initiatives. These are evaluated through a structured, time-bound prioritisation process that ensures alignment with national goals while reducing bureaucratic lags and delays. Cross-sector coordination units are being tasked to fast-track approvals, while ministries are developing streamlined licensing procedures and clearer regulatory pathways.

Somalia is changing the way it engages with its private sector. Rather than designing interventions in isolation, the government is actively seeking submissions from local and international businesses. These proposals are assessed for strategic relevance, feasibility, and public value. The government is not positioned as the lead investor or sole implementer. Its role is to facilitate, to clear pathways for licensing, land access, infrastructure, and regulatory approvals. This approach aligns state support with market readiness, ensuring that resources are allocated to initiatives with real momentum and tangible benefits.

However, at the crux of these grand plans lies the challenge of effective and efficient delivery. Delivery is often misunderstood as a complex, bureaucratic process that demands large monitoring units and layers of administrative oversight. In reality, effective delivery is about clarity, focus, and discipline. PEMANDU’s experience shows that a small, highly skilled delivery team can achieve far more than a bloated bureaucracy. The model is lean by design. It functions like a rapid-response unit, working across ministries to address specific challenges and deliver tangible results. The emphasis is not on building parallel systems, but on activating what already exists within government and accelerating the pace of execution.

Lengthy delays in securing permits, unclear tax systems, unpredictable regulations, and weak enforcement remain common obstacles. Somalia faces many of the same issues. What sets its National Transformation Plan apart is the way it chooses to address them directly and practically. At the heart of this approach is the Lab process, a working format that places government officials, regulators, and private sector leaders at the same table. Together, they identify the specific constraints holding back progress and work through realistic solutions within a defined time frame. Reform in this setting is not a distant or theoretical exercise. It is immediate, transparent, and shaped by those responsible for getting results

PEMANDU’s experience across more than a dozen countries underscores this point. Throughout over 15 years of running transformation across Africa: Djibouti, Senegal, Nigeria, Botswana, South Africa, Lesotho, Tanzania, Rwanda, Namibia, Uganda, Zambia, Ethiopia and now Somalia we have seen how the failure to implement reforms—despite extensive analysis and donor funding—undermines trust and progress. Lasting reform is rarely achieved through high-level strategy alone. The success of a development strategy does not rest on the volume of international conferences held or the number of frameworks published, but on whether it tangibly improves how a business gets a licence, builds a factory, pays staff, or exports a product. The Big Fast Results methodology is specifically designed for this, tried and tested across decades and governments. It is not about sweeping, top-down reform driven by external pressure, but grounded change led by domestic actors who are directly responsible for delivering it. This is where sustainable transformation begins.

Figure 3: PEMANDU’s Big Fast Results Methodology is designed to deliver results

In Somalia, this approach is already bearing fruit. With ministries now publishing sector priorities and investment gaps, the pathway for local businesses, philanthropies, and foreign investors to engage is clearer than ever. Importantly, this is not a static five-year plan. Built into the NTP are annual stocktakes, real-time delivery tracking, and ministerial performance scorecards, holding institutions accountable not by rhetoric, but by results. If the COVID-19 pandemic taught policymakers anything, it is that long-term strategies must be agile enough to withstand external shocks. The NTP reflects this reality. Rather than waiting for mid-term reviews, the performance cadence of the Delivery Unit enables weekly tracking of progress and bottlenecks, allowing the government to course-correct in real time. Even in areas affected by conflict, Somali enterprises continue to operate, underscoring the importance of enabling the private sector’s role in building national resilience. The task ahead is to remove the barriers that slow progress, embed a culture of responsiveness within government, and ensure that public systems keep pace with the entrepreneurial drive that has sustained Somalia through its most difficult years.

Across Africa, national development plans routinely emphasise the role of private capital, yet the mobilisation of such investment remains constrained by fragile governance systems and underdeveloped institutions. Recounting decades prior, countries across Asia faced similar postcolonial and post-conflict realities. In response, several adopted pragmatic policies that prioritised market reforms and forged close alignment between the state and the private sector. The result was a wave of growth across what came to be known as the Asian Tiger economies, with countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, and later others charting paths to industrialisation and rising prosperity.

Like Southeast Asia three decades ago, Africa is beginning to chart a new trajectory, one fuelled not by foreign aid but by ambition, entrepreneurial dynamism, and a growing desire to redefine its place in the global economy. While drawing lessons from Asia’s experience, Africa is also increasingly positioned to benefit from its capital, expertise, and evolving investment appetite. As the Global South reconfigures itself within a more evolving and multipolar international order, and as blocs such as BRICS gain renewed prominence, the case for a deeper Africa–ASEAN trade and investment framework grows stronger. Such a compact would not only expand economic cooperation but also signal a broader commitment to South-South solidarity in the pursuit of a shared prosperity.

Laying the Groundwork for a New Somali Future

Somalia’s National Transformation Plan marks more than a change in policy. It signals a deeper shift in mindset. By reclaiming national planning as a Somali-led and Somali-owned process, the country has taken a meaningful step toward shaping its own path. This is not a vision built on idealism, but one anchored in practical reform, real-time delivery, and inclusive participation. It acknowledges that resilience does not come from rhetoric, but from systems that work, institutions that adapt, and people who are empowered to deliver.

The road ahead will not be easy. But with the right structures in place, the right partners at the table, and the willingness to break from old ways of doing things, Somalia is laying the groundwork for a future defined not by fragility, but by self-determination and steady progress.

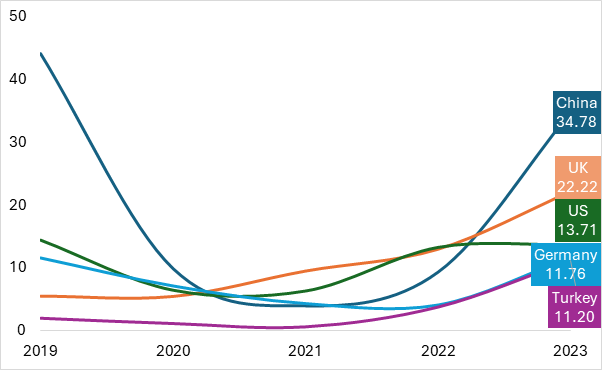

Source:

- CEIC data

- Ministry of Planning Somalia (2021)

- EY Global, Why Africa’s FDI landscape remains resilient (2024)