By Marc Fong

The Sultanate of Oman has had a long and rich history in the fisheries sector, with fishing activities taking place as far back as the birth of the Sultanate. Oman has the longest coastline amongst the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries with over 3,000km of coastline facing the Gulf of Oman, the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. In addition to this, Oman contributes to over 31% of produce amongst the GCC and is the only net exporter of fish in the region. Oman has a strong regional position but despite historical growth of 5% or more, the fisheries sector contributes less than 1% of GDP1 .

An analysis of the sector showed that fisheries in Oman is heavily reliant on subsistence fishermen who accounted for over 99% of production. Limitations on traditional methods and equipment, coupled with the need for additional capacity within regulatory authorities such as the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAF) to accurately define sustainable fishing levels meant that certain fish stocks were in danger of over-exploitation and potential collapse. In addition to this, with limited adoption of modern fishing technology, there is limited room for future growth.

Globally, aquaculture production is nearly on par with fish harvested from the wild but in Oman the aquaculture industry is minuscule. Similarly, fisheries processing and exports are largely limited to raw fish and primary processing with little value-add.

Despite these challenges, there remains significant room for growth in the Oman fisheries sector. Although it is the top producer in the GCC, analysis indicated that Oman is only addressing 2-3% of the total flora and fauna (biomass) in its seas. Furthermore, its long, largely undeveloped coastline with multiple coastal and water conditions are ideal for a variety of large-scale aquaculture projects. High levels of seafood-based processed products from neighbouring countries such as the UAE, which largely use produce imported from Oman, also indicate a potential to develop its downstream sector.

In 2017 MAF adopted a collaborative, result-driven approach for Oman with the introduction of the Fisheries Lab via PEMANDU Associates’ Big Fast Results (BFR) Methodology – 8 Steps of Transformation©. The lab focused on three key pillars; Catch (focused on tapping Oman’s natural biomass potential in the Gulf of Oman, the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean), Aquaculture (focused on developing higher-value aquaculture projects in collaboration with the private sector) and Processing & Exports (focused on downstream projects to add value to raw produce).

A bottom-up development of initiatives

Oman’s legacy with fishing meant that the sector had grown organically for centuries with minimal government intervention. However, the lack of associations or cooperatives – key features in developed nations – meant that growth was limited at an individual level with the vast majority of economic activity generated by individual fishermen using artisanal (traditional) techniques. It also meant that their issues and needs were not aggregated and channelled formally to the government, sometimes leading to interventions and initiatives that were incorrectly targeted.

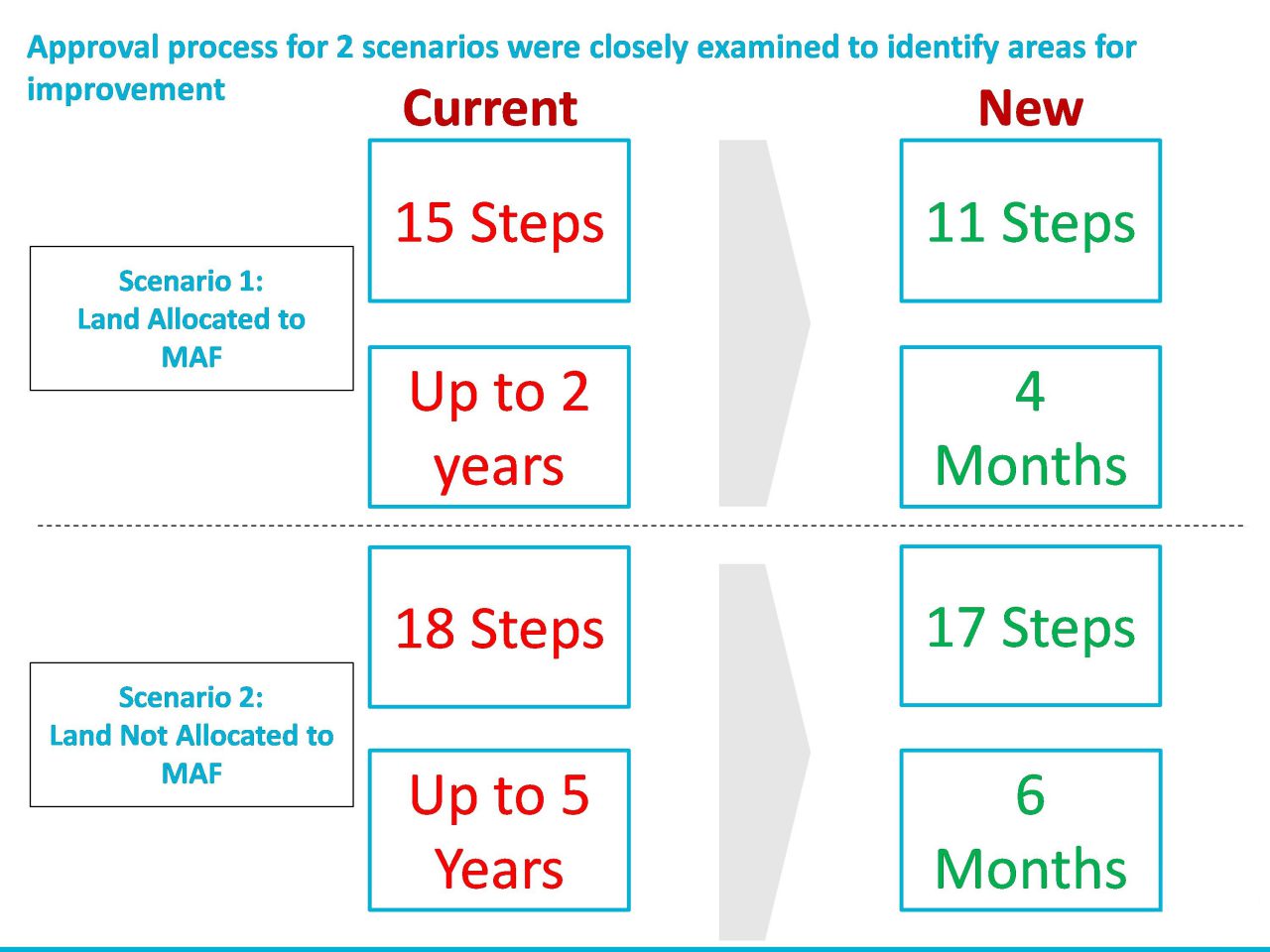

The lab ensured that voices from both traditional fishermen as well as private businesses across the Sultanate were collated, and top issues prioritised. This approach was instrumental in ensuring that the government was cognisant of key pain points in the overall value chain. For example, obtaining permits to utilise land for aquaculture was often a lengthy and arduous process – in some instances taking over five years and requiring documentation from four or more ministries.

This had the effect of deterring private sector interest in the sector, while the government lacked an aggregated voice to prioritise this issue for urgent resolution. Through the extensive consultation in the labs, the private sector was able to collectively demonstrate the vast potential of unlocking private sector investment into the aquaculture sector. The lab succeeded in obtaining agreement from key ministries for a greatly simplified land use approval structure, potentially reducing time taken for approvals by up to 90%.

The development of a National Fisheries Management programme also ensured that a longer-term view was adopted within the ministry to ensure the sustainable exploitation of fish stocks. Amongst others, this programme involved better and more regular mapping of existing fish stocks to ensure that clear fishing quotas could be set to maintain and grow the industry.

Additionally, the government was also better able to prioritise its resources. By understanding where the greatest demand for services was, the government was able to focus on developing ports in three key areas in three years instead of seven ports over a course of nine years. The ports were prioritised on the basis of identifying return on investment and number of fishermen served as well as potential flow of catch.

The net effect of this, coupled with other initiatives, succeeded in unlocking over 20 projects worth approximately OMR640 million (US$1.6 billion) in investment over five years, including the world’s largest shrimp farm in Bar-al Hikmah.

Balancing multiple objectives

The true north of the lab as well as the Economic Diversification Programme was economic growth. However, recent events in Oman placed pressure on the government to create large numbers of jobs for locals. This need presented a conflict as the majority of labour in the fisheries sector came from foreign (sometimes illegal) workers. Omanis were mostly averse to taking up fishing as a job as it was labelled as ‘3D’ (dirty, dangerous and difficult) as well as being a relatively lower-income job.

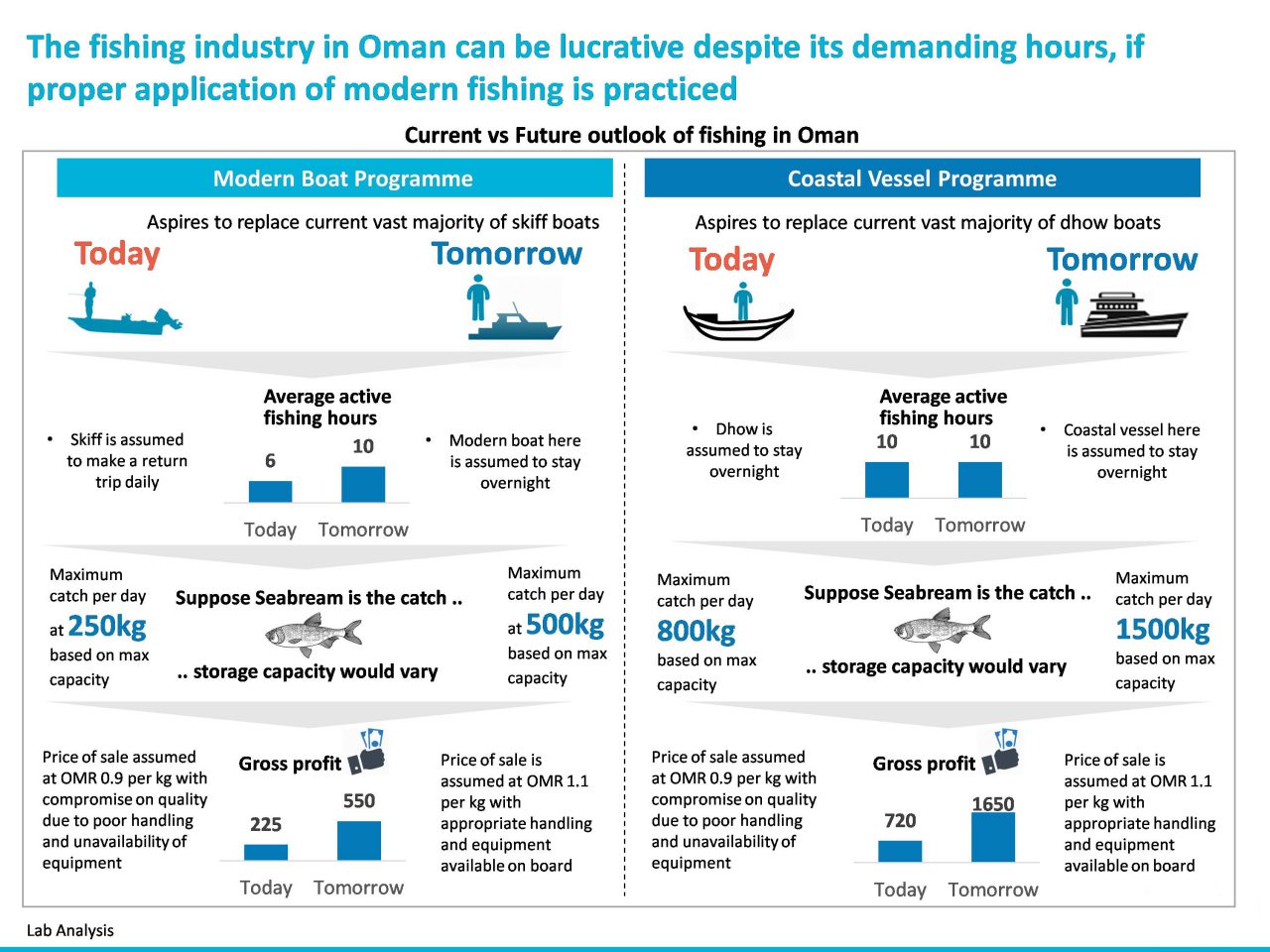

Ultimately, the government faced a trade-off. Mandating Omani jobs in the sector would increase costs (due to minimum wages for Omanis), reducing the competitiveness of the sector and potentially reducing productivity (due to labour shortages). The government reached a compromise with initiatives to modernise traditional fishing vessels which would improve working conditions and form fisherman’s villages to create a better living environment for fishermen.

Further to this, initiatives to promote modern fishing techniques as well as developing traditional fishermen were introduced, paving the way for access to deeper waters and larger as well as niche fish stocks. The National Fisheries Management scheme also greatly simplified fishing permit approval processes as well as committed government funds and institutions to providing co-financing for artisanal fishermen.

These initiatives were also complemented by over 20 private sector-led projects including an initiative for the private sector to co-develop training programmes and apprenticeships with the government. This aimed to ensure that Omanis were adequately equipped with modern technology and trained to pursue larger and higher value fish stocks.

In addition to this, the government had previously banned trawling – a commonly utilised fishing method – due to environmental concerns over damage to the sea bed and marine by-catch. New proposals for mid-water trawling – a technique used in developed countries such as New Zealand, Norway and Ireland – were also rejected due to fears over public sentiment regarding the term ‘trawling’.

However, through the lab’s data-driven analysis – identification of huge untapped fish stocks that this initiative would unlock, coupled with analysis on acceptable fishing levels and usage of modern monitoring technologies that would allow the ministry to monitor impact of the new techniques, eventually convinced the minister to allow a pilot project. The private sector’s strong commitment including allowing ministry officials to sail aboard the ships and the use of electronic monitoring devices on the trawling nets themselves gave the government a level of comfort to proceed with the trial.

With these initiatives in place, Oman’s fisheries sector is poised for the next phase of growth. A traditional fishing powerhouse in the Gulf region, the country’s shift to a private sector-led growth model has brightened its future.

1Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Oman. National Centre for Statistics & Information, Oman