Author: Aina Salleh

Data and research support: John Tan

Growing up in a Malaysian household means seeing your mom, sisters and aunties bustling in the kitchen, often while attending to crying children. We marvel at how well they multitask, seamlessly balancing cooking, cleaning and caregiving. While we often refer to this as a labour of love, it is crucial to recognise that it is also hard work – care work. Within the family and societal setup, this type of work is typically unpaid.

Care work encompasses the routine maintenance needed to sustain individuals, households and communities. It involves tasks like cleaning the house, bathing children, cooking for the family, or caring for an elderly parent. These seemingly mundane tasks are the bedrock of a functioning society and are essential for enabling participation in the economy. All of us have either performed or benefited from care work at different points of our lives.

The gendered burden of unpaid care work

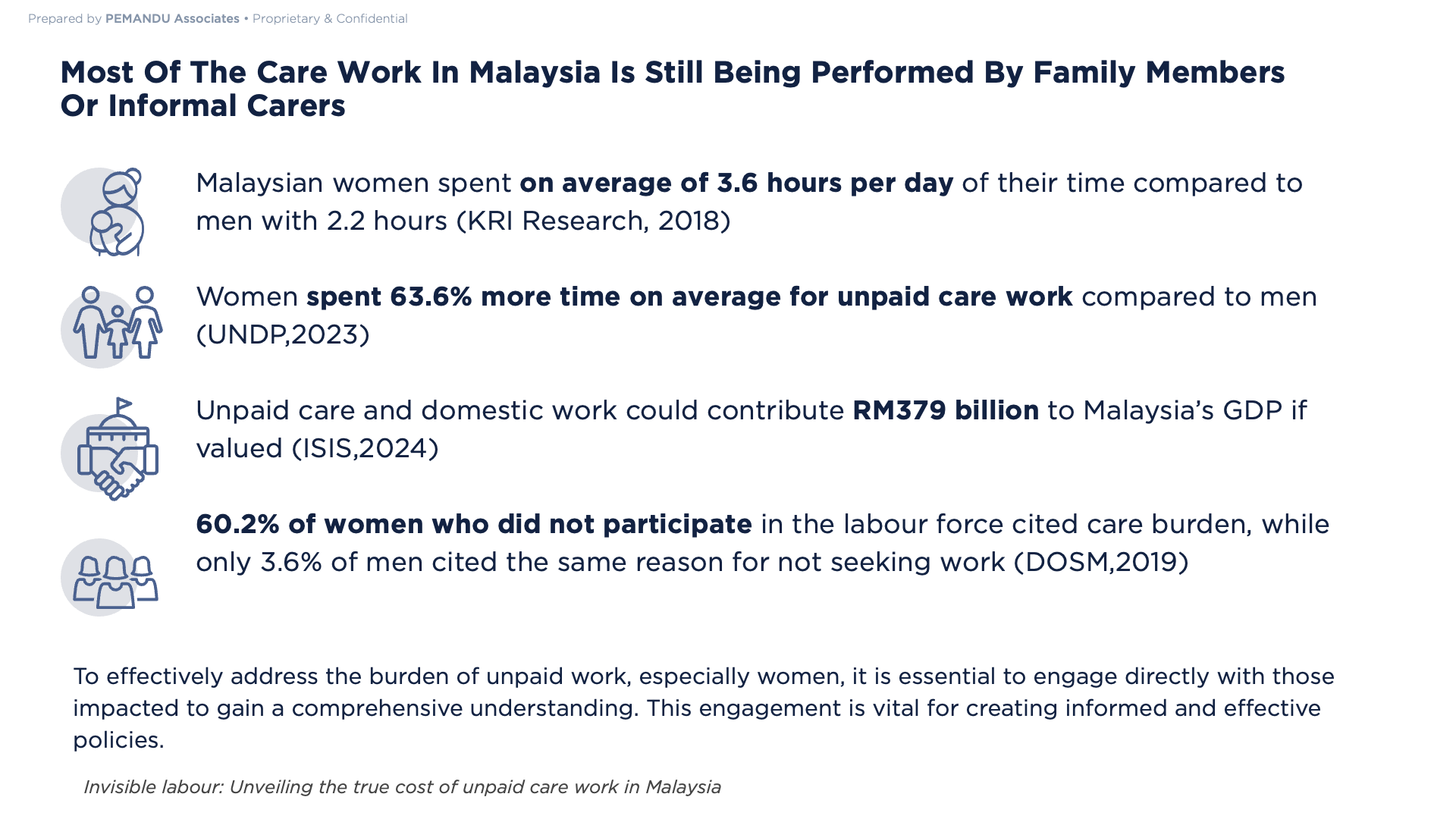

Unfortunately, the burden of unpaid care work disproportionately falls onto women due to a blend of historical and cultural norms, entrenched gender stereotypes, economic inequalities, insufficient support systems, and workplace inequities. Unpacking that will be a story for another day but suffice to say that women spent a disproportionate amount of their time quietly shouldering three quarters of the world’s unpaid work, according to International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Zooming in on Malaysia, 60.2% of women are not part of the workforce due to family-related responsibilities, as revealed by the 2018 Labour Force Survey Report. However, this does not mean that working women are exempt; many endure what is known as the “second shift,” where after clocking out from work, they clock in at home to handle another round of unpaid care work. Consequently, women are expected to work as if they don’t have families and care for their families as if they don’t have to work.

The second shift forces women to simultaneously carry the weight of productive and reproductive work, impacting their physical and mental health, limiting their career advancement opportunities, and perpetuating gender inequality in both the private and public spheres. This likely contributes to Malaysia’s persistently low female labour market participation rate of 55.8%, as of the latest Department of Statistics Malaysia data, despite women achieving high levels of education. In fact, Malaysia’s female labour market participation trails behind that of most ASEAN countries, ranking eighth out of ten, in a 2022 ILO report.

Millennials are being sandwiched between taking care of aging parents and providing quality childcare. This image is for illustration purpose only

Moreover, because care work is often excluded from national accounting data, society has become accustomed to the notion that caregiving is not “real work” and should not incur costs, often justified by familial obligations and filial piety. Conversations about outsourcing care, particularly for aging parents, are stigmatised and deemed shameful, despite the potential benefits of professional elderly care. Consequently, caregivers silently shoulder this burden, even without the necessary coping skills and mental resilience.

As Malaysia nears aged status by 2030 and the demand for care rises, it is time to have the difficult conversation: How long can we freeride on women’s unpaid labour as they step in as informal carers? Why do we typically pay for services like childcare and chores but fail to value them when they are performed at home? Most importantly, is this setup sustainable in the face of the looming care crisis, where the elderly population is projected to outnumber working-age adults soon?

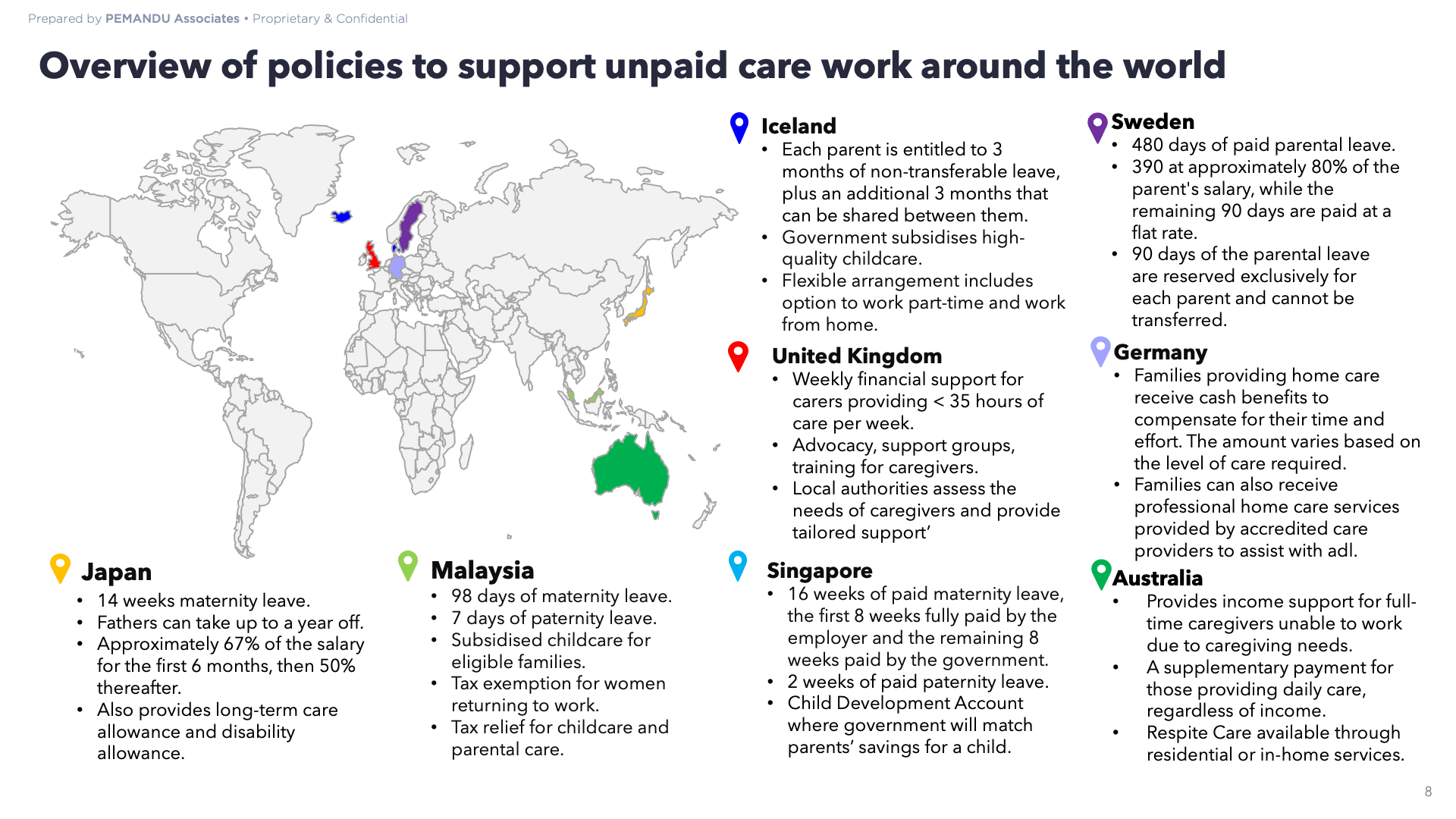

Of course, the obvious solution is to enact more policies. However, even the most egalitarian societies have not fully managed to redistribute the burden of care equally without unintended consequences. If we are not careful, we risk perpetuating existing inequalities or inadvertently creating new ones. In Scandinavian countries, comprehensive state-sponsored care often comes at the cost of high taxation. In Japan, generous parental leave policies have seen low uptake due to lack of societal perception change. Despite these challenges, there is a glimmer of hope as Malaysia observes and learns, having recently made significant efforts in addressing its own care needs.

Invisible labour: Unveiling the true cost of unpaid care work in Malaysia

The Care Industry Lab

In honouring its commitment to recognise, reduce, and redistribute the burden of care, Malaysia’s Ministry of Women, Family, and Community Development (KPWKM) recently engaged over 300 stakeholders in the care ecosystem. PEMANDU Associates had the incredible opportunity of supporting the Ministry through our signature Lab where key players rigorously identified challenges and co-developed 22 actionable policy solutions that will feed into the national care action plan.

Guided by aspirations of the MADANI Economy framework to enhance the quality of care for children, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities, as well as boost female labour market participation, the Lab was impactful for its grassroots approach driven by frontline caregivers, care centre operators, and non-governmental organisations. By engaging stakeholders through the Lab, KPWKM signified its willingness to take a non-prescriptive approach to addressing the care crisis, which facilitated in-depth discussions rooted in the real experiences of those on the ground.

The Care Industry Lab by KPWKM supported by PEMANDU Associates

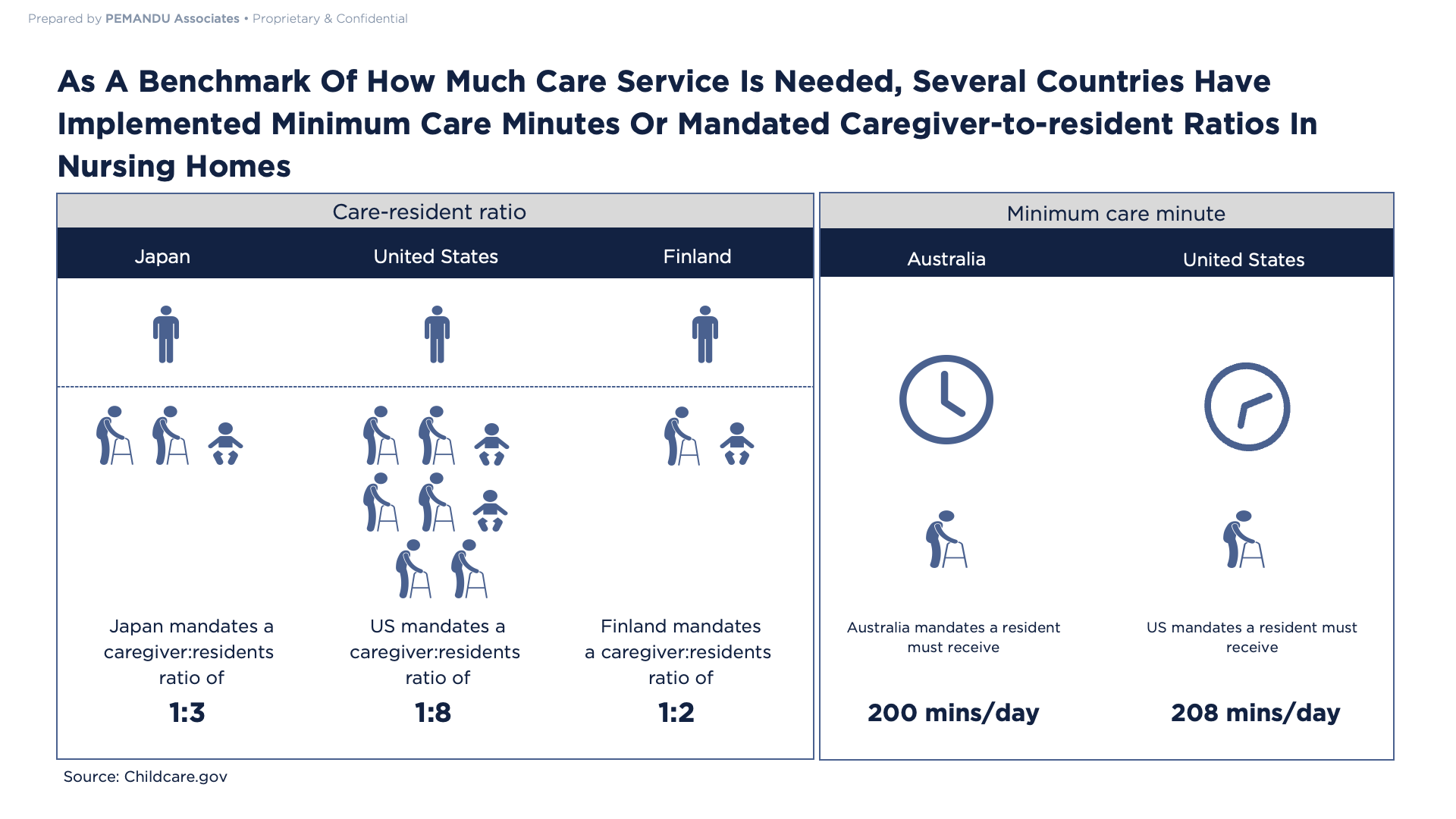

A critical pain point identified by the participants is the shortage of trained caregivers in the country. Despite being mostly unpaid, when care work is paid, it is too often undervalued and characterised by low wages, poor working conditions and the lack of career path. Therefore, caregiving is often perceived as gig work rather than a viable career option. The inability to attract and retain talent within the care sector further widens the gap between the demand for specialised care and the supply of skilled caregivers.

Need for Care: A summary of minimum care required as mandated in nursing homes in various countries.

Equally crucial is a comprehensive data collection mechanism to accurately assess the value of care work. Gathering precise information about the time dedicated to care-related tasks remains a costly and complex endeavour. Without such data, care work remains invisible in mainstream economics and policymakers struggle to accurately allocate resources to address various care needs. Failure of care systems often results in women stepping in as default caregivers without proper training and skills. Additionally, a recent study by ISIS Malaysia concluded that unpaid care and domestic work could contribute RM379 billion to Malaysia’s GDP if properly valued. This underscores the urgency to bring care work to the fore.

Discussions about supporting those burdened by unpaid care work also took centre stage. It is acknowledged that women continue to bear the brunt of this essential yet often unacknowledged labour at home. This imbalance underscores the necessity of redistributing care responsibilities to promote gender equality. Without proper support system and viable alternatives, women are very likely to suffer from caregiver’s burnout, a vicious cycle that affects not only their well-being but also the overall dynamics of care provision in society.

Support for informal carers: A summary of policies around the world to support those with unpaid caregiving responsibilities.

In short, addressing these challenges requires a concerted whole-of-society effort to implement policies that promote the equitable distribution of caregiving responsibilities. Challenging policy may be hard, but changing long-entrenched societal norms is even harder. Sweden is often held up as the gold standard for its generous parental leave policy, which has significantly encouraged men’s involvement in caregiving; however, this transformation took 50 years to achieve with the introduction of the Parental Leave Act in 1974. Nonetheless, policy nudges are a powerful tool to expedite narrative shifts, and we might as well start now.

Call to Action

So, let’s continue to have these difficult conversations, Malaysia. While change does not happen overnight, it is important to be proactive in laying down the foundations for a better functioning care system that recognise, reduce and redistribute care imbalances.

Engage with policymakers, support grassroots initiatives, and advocate for equitable care policies. Together, we can build a future where care work is valued and supported, ensuring a more balanced and fair society for all.

In addition to her expertise in the care economy Aina Salleh, a specialist at PEMANDU Associates, has delivered a compelling TEDx talk on “The Gendered Burden of Unpaid Care Work.” To gain further insights, you can view her talk here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zcC9M4QKlU