When PEMANDU started work on the National Transformation Programme (NTP) in 2009, we had two general sentiments beating down our front door – measured optimism and pure cynicism. The career cynics had zero faith that the NTP would deliver any impact, while the measured optimists were willing to give the Government a chance.

The NTP set out to address seven social issues that were of concern to Malaysians at the time. Subsequently, we identified 12 priority economic sectors with six policy enablers to grow Malaysia’s economy in a manner that is inclusive and sustainable, with the view of propelling the nation out of the middle-income trap into high-income status by 2020.

Today, as we enter the NTP’s eighth year, I wholeheartedly believe that all the Ministries, Departments, Agencies and private sector project owners involved have been steadfast in moving the country’s transformation forward, despite the naysayers. Steadily, the Government has delivered evident outcomes from its promises made under the NTP.

The results and challenges faced are evident in our six Annual Reports published since 2011. Let me highlight here, some of the key achievements to date. Chief among these was the launch of the much-anticipated Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Line 1 on 17 July 2017. I believe the MRT has ushered in a new era of public transport in Malaysia, where close to a million people can be transported over 100km daily in a fast, convenient and environmentally-friendly way.

Steps to revamp our education system, although a mammoth task, have also borne fruit. Our students are now progressively doing better against global benchmarks. The Trends International Mathematics and Science (TIMSS) study showed that Malaysian schoolchildren’s ability in those subjects improved significantly in 2015 from the last study in 2011. For Science, Malaysia was among 16 countries recording the highest score of 471, up from 426 in 2011, while for Mathematics our students recorded 465 points from 440 in 2011.

These initiatives, like other activities under the NTP, enable us to be competitive as we pursue our aspirations of becoming a high-income and developed nation. And even as we journey towards a new phase for Malaysia, we have ensured social issues, such as public safety, are not neglected. Since 2010, we have almost halved Index Crime to record a total decline of 47% up until 2016.

Underpinning these achievements has been our steady march towards high-income status. According to the World Bank, Malaysia’s GNI per capita amounted to US$9,850 in 2016, putting us within sight of its high-income threshold of US$12,235.

Indeed, we have been closing the gap between middle and high-income by leaps and bounds – in 2009 our GNI per capita was “stuck” at US$7,620, separated by a gulf of 34% from the World Bank’s high-income threshold. As at 2015 we bridged the divide to 19%, marking our move out of the middle-income trap.

For Malaysians, this translated into growth in the median monthly household income to RM4,585 in 2014 from RM3,626 in 2012, representing an increase of 11% annually. Additionally, we have succeeded in systematically reducing the incidence of poverty in our country to 0.6% as at 2014 from 3.8% in 2009.

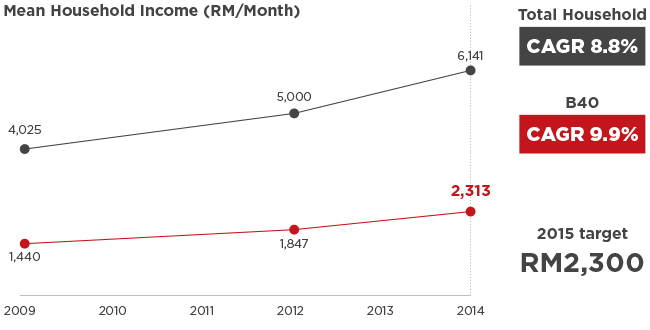

Even more heartening has been the income growth within income groups, with the bottom 40% of income earners (B40) charting the largest increase. Starting at a median and mean monthly income of RM1,440 in 2009, up until 2014 the group has recorded a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13% to RM2,629 in median monthly income, and a CAGR of 12% to RM2,537 in mean monthly income.

Furthermore, we surpassed our target of growing B40 mean monthly income to RM2,300 at 2015, as identified in the 10th Malaysia Plan, ahead of schedule in 2014 where we recorded RM2,313. The middle 40% of income earners (M40), have also seen their median and mean monthly incomes rising, at a CAGR of 9% each to RM5,465 and RM5,662, respectively.

Our target of growing the B40 mean monthly income from RM1,440(2009) to RM2,300(2015) was met in 2014, ahead of schedule.

NOTE: Data for 2014 Household income survey are based on interim report and inflation data for 2012 is based on CPI until August 2014

Source: 11th Malaysia Plan

Yet, the NTP’s high-income target is only one facet of the work that the Government has done to strengthen our domestic position – especially in the midst of a volatile global economy which has prevailed since 2008. Another design of the NTP, and I quote Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed, our International Trade and Industry Minister, “[The NTP] had turned the country from an input-driven, low-wage and low-skill economy into that which is innovative, technology-based and has value-added skills.”

For example, initiatives under the Oil, Gas and Energy NKEA are focused on growing the sector’s downstream segment, which can yield higher value as opposed to just relying on revenues from crude oil exports. One definitive project is the Pengerang Integrated Petroleum Complex (PIPC) in Johor, which houses PETRONAS’ Pengerang Integrated Complex (PIC) and Dialog Group Bhd’s Pengerang Deepwater Terminal (PDT). PIC is the single largest downstream/infrastructure investment project in Malaysia and continues to progress well towards its full completion by 2035. PIC reached 50% completion as at the end of 2016, while the construction of phase two of PDT is underway following the completion of its first phase.

The NTP is also anchored on raising Malaysia’s global competitiveness, as the size of our domestic market caps the growth potential of local companies. To this end, we introduced competition laws, are driving the adoption of global standards to enable our local products to compete in the international market, and liberalised selected industries and sectors to create an environment conducive for business.

Collectively, our efforts have garnered Malaysia global attention and recognition – The IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook ranked Malaysia 14th out of 61 countries in 2016 from 18th of 57 countries in 2009 and since mid-2015, Malaysia has received an ‘A-’ sovereign rating and stable outlook from Fitch Ratings, which was maintained in October 2016 despite the tough year for all.

As we pick up our stride in 2017, I ask for Malaysians to keep their belief and hope for our country strong. Dispense with the noise and focus our energy on the work to deliver our high-income nation target. We still have a lot of work ahead of us to achieve our targets but we are seeing evident outcomes from the roadmap we first published in 2010.

Every year, we publish a detailed document of what has been achieved under the NTP, the KPI scores and traffic lights on items where we met targets (green), missed targets (red) and partially met targets (amber). For readers interested in these details, please visit the Download Centre to view the annual reports.