By Dr. Sarinder Kumari & Dhanendra Sivarajah

Agriculture quality standards have become imperative not only to ensure safe and quality products but also for farmers to access international markets.

A highlighted by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and academicians, tariff barriers have been replaced by sustainable requirements for market access as a means of protecting domestic producers. Understanding the requirements of the importing country and ensuring these elements are incorporated and harmonised with the standards of the importing countries is key as defined by the WTO Technical Barriers to Trade, an agreement which strongly encourages members to base their measures on international standards as a means to facilitate trade. Hence, it is essential for Malaysian farmers to practice Good Agriculture Practices that are aligned with international standards to access these markets.

These standards were introduced in accordance with Malaysian Standards that define processes in resource management for good and sustainable agriculture production which improve farm productivity and ensure produce is safe and of quality, with the welfare and safety of workers taken into account.

Spearheading a new approach to standards adoption

However, the introduction of the local standards brought on a different set of challenges. Among those highlighted by the farmers were limited market access, insufficient capacity building programmes to assist in compliance to standards, as well as questions from the importing countries on the standards applied. The value of certification was also questioned by farmers who saw the exercise as adding more work to an already laborious industry. Consequently, farmers were selling to middle-men, often at a minimal price, who were able to stretch their own profit margins through with their ability to penetrate the hypermarkets and as well as the export market.

To overcome these challenges, a mini-lab facilitated by PEMANDU Associates (during its time as a Delivery Unit in the Prime Minister’s Department) in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture was held, involving farmers associations and other relevant agencies. It was decided in the mini-lab that a rebranding of all three schemes under a single brand name was to be introduced to create a brand name that is easily recognised in the foreign market – this standard would also be harmonised with all other good agricultural practices used by other countries for the export market.

Thus, a series of focus group meetings chaired by the Undersecretary of the MOA as well sessions with the then-Minister of Agriculture, led to the birth of the Malaysian Good Agricultural Practices (myGAP) in 28 August 2013. Since then, myGAP has become known internationally and is synonymous with other standards such as GlobalGAP, JGAP (Japanese certification) and China GAP (China certification), to name a few.

Further to this, the MOA and its respective agencies also stepped up efforts in educating the public on the importance of certification to ensure sustainability, quality and lastly to also allow for market access, with the respective departments aggressively involved in promoting myGAP in their bilateral talks for market access. All main initiatives and sub-initiatives had individuals accountable for its implementation who were able to provide regular and comprehensive progress reporting.

Breathing new life into Malaysian produce

After the launch of the myGAP Certification and its brand promise of “Producing More, Improving Lives”, the MOA continued to work with various stakeholders to not only educate the farmers about the need and benefits of myGAP, but also encourage them to look beyond just farming but towards creating a safe and sustainable community. In an effort to further enhance the standards usage among farmers, MOA also allocated funds to assist farmers in upgrading their storage, sewage, collection, and other facilities that are requirements under the myGAP certification programme. Besides funding assistance, farmers also benefited from capacity-building programmes, awareness and promotion programmes.

The capacity-building programmes involved educating the farmers on the requirements of myGAP and its importance, which was then followed by assistance in completing the checklist in preparation for compliance and audit. This effort encouraged strong participation from farmers who were keen to understand the certification process.

Mr. M. Kaliyannan, who puts his customers at the top of his priority, has adopted myGAP in his 39-hectare watermelon farm to ensure higher standards of quality and safety for his crops. With myGAP, he has been able to widen his market for Grade A watermelons to foreign markets such as Dubai and Hong Kong. His revenue has increased more than 20% when compared to before myGAP.

“Under myGAP, there are many practical steps to follow including staff training, usage of pesticides, safety, and best practices for planters. I’ve seen many positive results since the adoption of myGAP.

“My ambition is to be the king of watermelon in Malaysia by exporting my entire Grade A products to the rest of the world. The myGAP programme is a good initiative, especially to assist us in the agriculture sector shared. I would definitely continue to encourage other farmers to follow my steps so that they can be successful as well,” he says.

Beyond addressing the supply side, the MOA also worked with hypermarkets in running awareness campaigns and promoting certified produce to encourage consumers to demand for produce that are certified. This has resulted in benefits for farmers by leveraging hypermarkets as a means of directly accessing the customer and avoiding the middle-man, and MOA’s efforts in increasing the number of certified farms in Malaysia.

Giving farmers a leg up into foreign markets

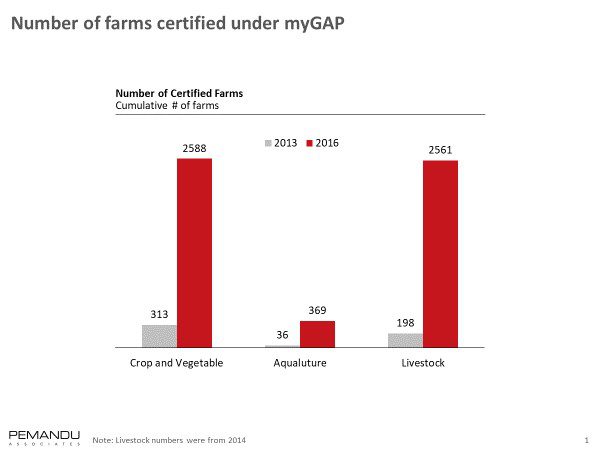

In 2017, with the introduction of myGAP, the cumulative number of farms certified with myGAP increased by 451% from 1,378 farms in 2011 to 6,226 farms in 2017, as more countries require the certification for the export of fruits and vegetables. Brunei become the most recent adopter of the certification, starting in January 2018. There was also an increase in the number of livestock farms were certified by the Department of Veterinary Services, as China, a major market for edible birds’ nest, started making it mandatory for bird’s nest imports from swiftlet farms to be myGAP certified, further proving that adopting international standards does help secure local exporters’ market penetration.

To further strengthen the transition to a globally accepted standard, the Ministry included routinely monitored KPIs that trigger problem-solving sessions which allow for effective intervention. The result of the effort is felt by the operators, as demonstrated by the following feedback received in a survey commissioned by Standards Malaysia back in 2014:

Farmers acknowledged that myGAP propagates prudent and economical administration of chemical fertilisers, which in turn helps check/control pest infestation, contributing to increased yield and reducing cost.

The feedback obtained from the farming community shows that while the process of converting from a local to a global standard does come with a learning curve and temporary pain points, the benefit of securing market access and improving profits is well worth the investment. The transformation to the global standard was made possible by bringing the public and the private sector together to problem-solve anticipated issues for the conversion, and relentlessly monitoring the work toward a common purpose.

“Before I adopted myGAP, I had to spend about RM16,000 on chemical fertilizers, but after the adoption, I was able to save money because I only spent RM2.000 by using the Sri Product via the Natural Farming concept. Now, I am using 70% of Sri Products and 30% chemical fertilisers. With myGAP, I am able to sell my rice for RM6.00/kg compared to before when it was only RM2.00. I have also sold rice seeds to Sendi Enterprise for RM1,350/tonne and sold rice at RM1,200/tonne to Bernas.” – Abdul Razak Chik, better known as ‘Pak Lang Sri’, who owns a paddy farm in Sekinchan, Selangor.