When the idea to build a Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) in Malaysia was first put on the table in 2010, it was met with varying degrees of both resistance and cynicism – resistance from pockets of community where the rail system would pass through, and cynicism that it would take the government of Malaysia a lifetime to get its act together.

They were wrong. It took Malaysia only six years to build and develop an entirely new rail line and integrate it into the existing system. The MRT is one of the country’s largest single investments and was intended to radically improve and transform Kuala Lumpur’s inadequate public transportation coverage. It was meant to propel the Greater Kuala Lumpur metropolitan area to be on par with that of developed cities around the world. Today, the MRT has managed to deliver both and has quickly become a popular mode of transport to get in and out of the city centre for residents and tourists alike.

Historically, public transport systems in Malaysia functioned largely as part of the social safety net for those with no other means of getting around. These included people from low-income households (B40) as well as those with lesser means to get around. This is slowly beginning to change with the growing demand amongst city dwellers wanting to go carless. The transit system of the future will be for people across the board. And today, the MRT moves an estimate of 196,000 people daily.

Malaysians already have access to a range of public transportation in the Klang Valley, from several bus operators, three light rapid transit (LRT) lines, two commuter rail lies, one monorail line, to an airport rail link. But as the city grows, so does the number of commuters travelling between the city and surrounding suburbs. Delivering a reliable and modern mass rail transit that elevates the current public transport system could not have come soon enough.

Meeting a need

It was estimated in 2017 that about 1.1 million people travel by public transport every day, most of them travelling in, out and around the Greater Klang Valley area. The Klang Valley itself is home to about 725 million people; it’s a rising urban hub and the site of one of the worst traffic jams in the country. A study by Boston Consulting Group showed that Malaysians spend an average of 53 minutes in traffic and 25 minutes to look for parking each day. That’s a significant portion of time of the day spent stuck in a traffic jam and this adds up depending on how far Malaysians have to travel for work or to school.

In an attempt to ease traffic congestion and offer more transport options to commuters, the government made urban public transport a priority area. Prior to this, the last major upgrade to Malaysia’s public transport infrastructure was the introduction of the LRT in the late 1990s and the monorail in 2003. The LRT is still one of the more popular railways in the country but limited stations and overcrowding during peak hours makes the line inaccessible for many Malaysians.

The MRT was launched to address these concerns. The first line, stretching from Sungai Buloh to Kajang, connected 44 shopping centres, 11 education centres and several hospitals and was completed in 2016. In terms of integration, the MRT has been seamlessly connected to the existing public transport system, with paid-to-paid walkways and connections linking the MRT Line 1 to LRT, KTM and monorail lines. As the other MRT lines are built, more stations will be integrated into the overall Klang Valley rail network.

Providing an alternative choice of commute

Introducing the MRT extends the public transport coverage to more neighbourhoods and suburbs who, prior to the MRT, did not have easy access to a train station. It has given more people more choices on how to get in and out of the city centre and made public transport equally accessible for all.

Introducing the MRT extends the public transport coverage to more neighbourhoods and suburbs who, prior to the MRT, did not have easy access to a train station. It has given more people more choices on how to get in and out of the city centre and made public transport equally accessible for all.

A study by the Centre of Governance and Political Studies (CENT-GPS) pointed out that many of the MRT stations were built adjacent to higher-income neighbourhoods, arguing that this was why the MRT was not as popular as anticipated. However, the study assumed that only middle- and lower-income households take public transport; this isn’t necessarily the case. More Malaysians from all backgrounds are choosing not to drive to work, whether to avoid the city centre’s infamous traffic jams, because they’re becoming more environmentally conscious or simply because there are more options now.

It’s also pretty cheap to ride the MRT. The price of MRT fares is comparable to the LRT and is actually lower than the Sunway BRT, with concession rates for senior citizens, students and people with disabilities. There’s also a second option, introduced early this year. Understanding that the concession cards cater to only a fraction of the population who take public transport, the government introduced two monthly travel passes, one at RM100 and another, just for buses, at RM50. The cards were extremely well received by the public; ridership on all rail lines surged by 40% surge in ridership after the travel cards were introduced.

Is the MRT for everyone?

One of the key characteristics of good public transport is accessibility – stations must be accessible for everyone, especially for people with disabilities or senior citizens with mobility needs. In 2017, over 450,000 people registered as Persons with Disabilities (PWD) with the Department of Social Welfare. 35.2% were PWDs with physical disabilities. Earlier stations were not built to cater their needs, causing disabled commuters to feel marginalised.

One of the key characteristics of good public transport is accessibility – stations must be accessible for everyone, especially for people with disabilities or senior citizens with mobility needs. In 2017, over 450,000 people registered as Persons with Disabilities (PWD) with the Department of Social Welfare. 35.2% were PWDs with physical disabilities. Earlier stations were not built to cater their needs, causing disabled commuters to feel marginalised.

However, focus was aimed at increasing public convenience for all – including the disabled community. The government ensured that all MRT stations were constructed to be disabled-friendly and upgraded LRT stations along the Ampang and Kelana Jaya lines in July 2011. Today, most if not all stations are equipped with features like elevators and tactile paving. The gap between the train doors and MRT platforms has been designed to ensure that a wheelchair can roll in easily.

The Challenges – Today & Tomorrow

Urbanisation is on the rise as a truly global phenomenon as more people around the world are living and working in cities. This growing trend makes it even more important that cities transform to support the greater mobility requirements of urban dwellers. But creating the perfect public transportation network isn’t easy. Designing urban transportation for today’s cities has become highly complex; planners must balance the different modes of transport and a multitude of stops, while ensuring that the network can handle the amount and variety of traffic a good-sized city sees every day. While the focus of urban transportation traditionally is on residents, cities today are becoming hives of commerce and economic activity with residents, non-residents and travellers alike converging into one place. This makes having that public transportation network even more important for convenient mobility.

Malaysia’s public transport system is still a work in progress. One of the more valid criticisms in recent times given by Malaysian users on the urban transport system has been the poor first and last mile connectivity, with stations lacking safety measures such as dedicated pedestrian walkways on the streets closest to the station. This doesn’t just affect the MRT but also can be said of the other rail stations in Malaysia – a common complaint describes crossing the last 100 metres to get to a train station as “a nightmare”. The government has addressed this by introducing a feeder bus system to provide that last mile connectivity between MRT stations and neighbourhoods. The fares for all MRT Feeder Buses have been set to RM1, making them a very affordable option for commuters. However, more could be done to improve the efficiency of this feeder bus system and increase safety standards for pedestrians.

Another common perception is that few people take the MRT. As evident, MRT ridership is still growing. As of March 2019, the MRT operator reported that January’s passenger traffic for the MRT surged by 40%. Even if the increase rate drops back to the 28% yearly increase, it’s very likely that the MRT would reach the 250,000 ridership target before 2021. Moreover, the MRT is doing better than the LRT and Monorail lines who are both experiencing a decrease in ridership.

Integrated public transit systems are a big investment to build, operate and maintain to remain relevant to urban mobility. Introducing travel passes, electronic tickets and cashless systems have made Malaysia’s public transportation more convenient, but there are still more ways to encourage regular uses. For example, the rising demand for loyalty rewards programme and incentives, like the use of a point system based on trip miles, for commuters could be a way to promote the use of public transit and to influence consumer behaviour. Another thing to think about is using technology like phone apps to give commuters live traffic updates of the train and bus schedules for each line.

And this doesn’t have to come at the cost of taxpayers’ money; a study noted that for every USD$1 invested in public transportation, approximately USD$4 in economic returns are generated, and for every USD$1 billion in investments in the sector, 50,000 jobs are created and supported. The reasoning is that as more people cluster in a city centre, more jobs are created which would ultimately boost both wages and economic productivity over time.

Looking ahead

The MRT system is only two years old; it would take a few more years and the addition of the other two planned lines for it to reach its full potential. Cent-GPS concluded its report by stating that “the project was in the right place, it was in keeping with a greener future, it had the right idea for a sharing community.”

The MRT system is only two years old; it would take a few more years and the addition of the other two planned lines for it to reach its full potential. Cent-GPS concluded its report by stating that “the project was in the right place, it was in keeping with a greener future, it had the right idea for a sharing community.”

We agree. The MRT project was designed to provide a cheaper, greener, more convenient alternative to driving and it has delivered on its promise. Effective transportation makes cities more liveable by easing residents’ commute and transportation needs and increasing accessibility. For those who can’t or don’t drive, public transportation allows them to go to work, to school, to buy groceries or seek medical help, or just visit friends without having to ask for a ride or spend more to take Grab.

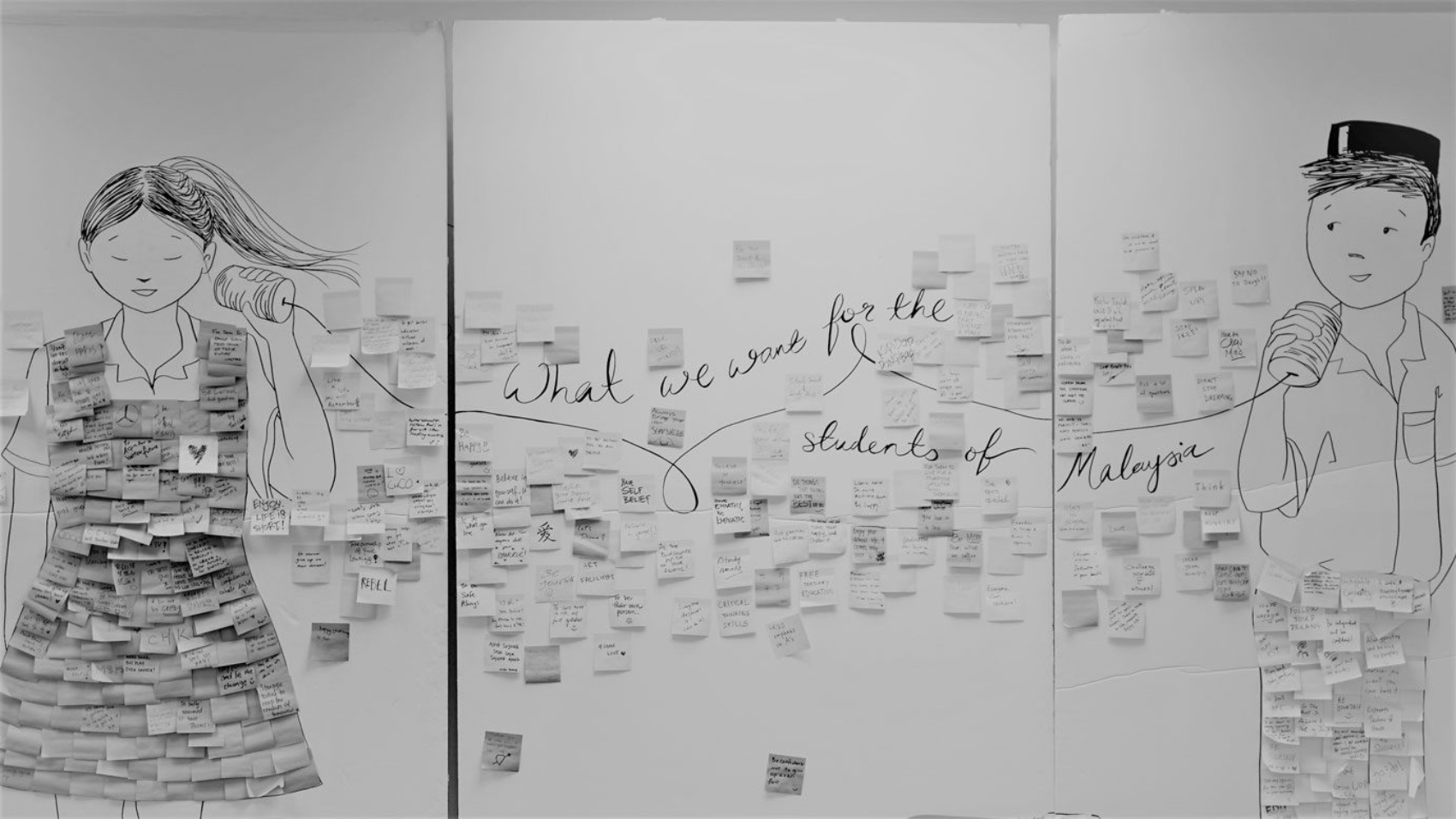

Moving forward, perhaps the time has come for the Ministry of Transport to conduct a country-wide stock -take of user needs, compatibility, trends and incentives to drive the next wave of urban public transport initiatives. It is after all almost 10 years ago, since this agenda was put under the microscope of the BFR Lab Methodology.

Claudio Seebach, from the President’s Delivery Unit in Chile, remarked that “on one side, stretch targets help persuade people to work hard to get things done. But on the other side, you can aim too high and miss, or if communicated badly, people take what you achieve for granted so it is a fine line to tread. This means that you also need clear accountabilities – so everyone knows who is doing what.”

Claudio Seebach, from the President’s Delivery Unit in Chile, remarked that “on one side, stretch targets help persuade people to work hard to get things done. But on the other side, you can aim too high and miss, or if communicated badly, people take what you achieve for granted so it is a fine line to tread. This means that you also need clear accountabilities – so everyone knows who is doing what.”

Acting more like policy SWAT teams deployed to expedite results, delivery units aren’t meant to change a whole country overnight. Their value lies in getting specific policies implemented and changing the culture of a government towards one that is results-driven, accountable and transparent. They can be used to break stakeholders out of their silos and bring them together to work on one common goal. Used correctly, the delivery unit can be a government’s best tool to bridge the implementation gap.

Acting more like policy SWAT teams deployed to expedite results, delivery units aren’t meant to change a whole country overnight. Their value lies in getting specific policies implemented and changing the culture of a government towards one that is results-driven, accountable and transparent. They can be used to break stakeholders out of their silos and bring them together to work on one common goal. Used correctly, the delivery unit can be a government’s best tool to bridge the implementation gap.

Introducing the MRT extends the public transport coverage to more neighbourhoods and suburbs who, prior to the MRT, did not have easy access to a train station. It has given more people more choices on how to get in and out of the city centre and made public transport equally accessible for all.

Introducing the MRT extends the public transport coverage to more neighbourhoods and suburbs who, prior to the MRT, did not have easy access to a train station. It has given more people more choices on how to get in and out of the city centre and made public transport equally accessible for all. One of the key characteristics of good public transport is accessibility – stations must be accessible for everyone, especially for people with disabilities or senior citizens with mobility needs. In 2017, over 450,000 people registered as Persons with Disabilities (PWD) with the Department of Social Welfare. 35.2% were PWDs with physical disabilities. Earlier stations were not built to cater their needs, causing disabled commuters to feel marginalised.

One of the key characteristics of good public transport is accessibility – stations must be accessible for everyone, especially for people with disabilities or senior citizens with mobility needs. In 2017, over 450,000 people registered as Persons with Disabilities (PWD) with the Department of Social Welfare. 35.2% were PWDs with physical disabilities. Earlier stations were not built to cater their needs, causing disabled commuters to feel marginalised. The MRT system is only two years old; it would take a few more years and the addition of the other two planned lines for it to reach its full potential. Cent-GPS concluded its report by stating that “the project was in the right place, it was in keeping with a greener future, it had the right idea for a sharing community.”

The MRT system is only two years old; it would take a few more years and the addition of the other two planned lines for it to reach its full potential. Cent-GPS concluded its report by stating that “the project was in the right place, it was in keeping with a greener future, it had the right idea for a sharing community.”

The reality we face is that addressing climate change isn’t going to be free or easy; it will take making some very tough choices every day for things to change. As the debate over the Green New Deal rages in the US, other countries are beginning to push their versions of a new green agenda.

The reality we face is that addressing climate change isn’t going to be free or easy; it will take making some very tough choices every day for things to change. As the debate over the Green New Deal rages in the US, other countries are beginning to push their versions of a new green agenda.  In October 2018, the United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a

In October 2018, the United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a

It’s been about a year and a half since the lab took place. To say that this lab has irrevocably changed the future of Malaysia’s forests would be a bit of a stretch – much still needs to be done and new policies would need to be drawn up and enforced.

It’s been about a year and a half since the lab took place. To say that this lab has irrevocably changed the future of Malaysia’s forests would be a bit of a stretch – much still needs to be done and new policies would need to be drawn up and enforced.

Most often, we have teachers, universities and employers pointing fingers at each other trying to blame the other for producing sub-par graduates. While employers often blame the educational system as a whole for not adequately preparing graduates for the workforce, some of that blame comes down on the students themselves for being unwilling or unable to perform suitably.

Most often, we have teachers, universities and employers pointing fingers at each other trying to blame the other for producing sub-par graduates. While employers often blame the educational system as a whole for not adequately preparing graduates for the workforce, some of that blame comes down on the students themselves for being unwilling or unable to perform suitably. Youth today are fully conscious of the difficulty of finding a job after graduation. Many are disillusioned with the fact that despite getting top-quality education from a good university, the chances of getting a job remain a challenge, let alone a well-paying one. Even a foreign degree, once coveted and sought after by Malaysians, is no longer a guaranteed path to a well-paying job.

Youth today are fully conscious of the difficulty of finding a job after graduation. Many are disillusioned with the fact that despite getting top-quality education from a good university, the chances of getting a job remain a challenge, let alone a well-paying one. Even a foreign degree, once coveted and sought after by Malaysians, is no longer a guaranteed path to a well-paying job.

However, one thing to note from all this is that our youth are resilient. We are seeing a higher rate of entrepreneurship and volunteerism amongst young people in Malaysia who see these activities as a viable alternative to the traditional nine-to-five job.

However, one thing to note from all this is that our youth are resilient. We are seeing a higher rate of entrepreneurship and volunteerism amongst young people in Malaysia who see these activities as a viable alternative to the traditional nine-to-five job.