By Yong Yoon Kit and Jade Swan E

In 2010, the global cruise tourism industry was looking to Asia as a major growth engine, with cruise passenger arrivals growing 7% per annum, more than double the annual international tourist arrivals of 3% from 1990 to 2008. However, Malaysia was not capitalising on this opportunity.

Many global cruise itineraries bypassed Malaysia’s ports, mainly due to the lack of terminal infrastructure and quality shore excursion tourism products and services that met the requirements of the cruise operators. This, in turn, was a result of stakeholders working in silos, causing inefficiencies and wastage of time to tourists, as they are unable to provide a seamless experience to tourists. Ultimately, Malaysia was deemed unattractive as a cruise destination. In contrast, neighbouring Singapore had invested heavily in developing cruise tourism, thus successfully securing its position as a home port, where vessels choose to base their operations, in the Southeast Asian region.

In an effort to improve the sector’s prospects in Malaysia and harness the potential of the global cruise tourism industry, the development of the Straits Riviera cruise playground was proposed as part of the Tourism National Key Economic Area (NKEA) under Malaysia’s National Transformation Programme implemented from 2009 to 2017. Anchored on five main ports; Penang, Sepang, Melaka, Tanjung Pelepas and Kota Kinabalu, the project also aimed to revitalise port cities with a focus on waterfront areas and identified supporting tourism sites. To ensure the success of the project, Malaysia needed to improve its terminal infrastructure, cruise tourism experience and governance & coordination.

Enhancing the Cruise Tourism Ecosystem

The Cruise and Ferry Integrated Seaport Infrastructure Blueprint for Malaysia was commissioned by the Economic Planning Unit in 2011 in collaboration with the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture (MOTAC), detailing the vision and policy for cruise industry development in Malaysia until 2020. This blueprint considered the infrastructure development and improvement plans for each key cruise terminal and port, making recommendations to reinforce theme-based cruise circuits as well as community-based infrastructure, perimeter attractions and connectivity.

The blueprint identified six ports as having potential to contribute significantly to the Malaysian cruise industry. These six ports were Penang, Port Klang, Kota Kinabalu, Langkawi, Malacca and Kuching. These ports had existing cruise infrastructure, a network of cruise arrivals and/or access to immediate tourism products. In 2013, Kuantan port joined the line-up of primary ports due to its growing strategic importance for international cruise lines developing their East Asia sectors. Kuantan’s emergence as a core port supported a projected traffic increase of cruises to the countries along the eastern coast of Southeast Asia, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

All these 7 ports were suitable as call ports, as identified in a white paper by the Asian Cruise Association (ACA) in 2013. Call ports need not necessarily be infrastructure heavy and only require an adequate wharf facility such as enough coaches to bring passengers to shore tour destinations, access for buses as close as possible to the wharf or jetty and a variety of sights, attractions and shopping areas within driving distance of the port. With regard to becoming home ports, Kota Kinabalu, Port Klang and Penang had the highest potential as these ports had capability for berthing alongside the wharf with adequate length and draft, road access and a secure perimeter.

With some expansions, these ports would have efficient terminals to process passengers and baggage and to provision vessels. These ports were also well-positioned with adequate air connectivity between turnaround city and source markets and were reasonably close to local airports, with sufficient access to ground transportation to handle the potentially large volume of passenger movements. Hotels were available for pre- and post-cruise overnights for guests coming from afar. The ports could also potentially capitalise on income from their terminal buildings through mixed-use developments combining cruise terminals, function and conference centres, restaurants and/or shopping complexes, thus allowing infrastructure investments to provide recurring earnings throughout the year.

In April 2011, the Ministry of Transport and MOTAC formed the Malaysia Cruise Council, a public-private stakeholders’ advisory committee, to address the lack of coordinated focus on cruise industry development. Co-chaired by the Secretaries General of both ministries, this council gave a coordinated voice to provide the direction for policies, developments and framework required by the cruise industry in Malaysia.

Sub-task forces were also formed for each of the seven primary cruise ports in Malaysia with representatives from local port authorities, agencies and private sector cruise industry players to address port specific issues and develop focused initiatives which also covered land-side attractions.

The setting up of these sub-task forces saw that operational matters were streamlined, and ports were also better positioned with international cruise terminal operators. One such success was the coordination of business owners to be located near cruise berthing areas, thus increasing tourist access and boosting spend.

To encourage foreign cruise vessels to provide services between Malaysian shores, the Cabotage Policy was gazetted in March 2012 to exempt all cruise vessels. This Policy previously only allowed for vessels that were registered in Malaysia to load and unload passengers in the ports of Malaysia. With this exemption, international cruise ships were able to disembark and re-embark passengers at more than one Malaysian port in any of its stopover destinations.

Breaking Down Silos

While these policy and governance issues were being addressed, MOTAC and the various State Tourism Boards continued to work with cruise terminal operators to promote their surrounding attractions and work with local tour operators to better develop targeted cruise tourism products. With the support of PEMANDU Associates (then known as PEMANDU, a delivery unit within the Prime Minister’s Office), Tourism Malaysia also worked closely with the lead agencies of each sub-task force to market their respective destinations at notable international cruise conventions such as Cruise Shipping Miami and Sea Trade Asia, and to engage regional cruise liners at these conventions.

Despite the facilitation provided, there were still many challenges as many ports were catered towards commercial activities with cruise handling still relatively new. Therefore, a Cruise Berth Allocation Workshop was conducted in 2015 to provide clarity in terms of general timelines, processes and persons responsible for berth arrangements at both dedicated passenger terminals and commercial ports.

From the workshop, different process flows were developed to address the needs of the different types of terminals, i.e. passenger terminals, cargo terminals and destinations with no port infrastructure. With the standardisation of SOPs across the board, both the authorities and the private sector cruise industry players had a clear understanding of the processes in place and were able to plan based on arrivals up to a year in advance.

The breaking down of silos between the multiple stakeholders involved marked one of the key achievements of this concerted effort to develop the cruise tourism industry. In May 2013, the inaugural Malaysia Cruise Industry Workshop was held in Penang in collaboration with the Cruise Liners International Association (CLIA) Asia.

The workshop marked a milestone as it was the first-time key decision-makers from international cruise lines and local industry players were able to directly engage with one another. It was attended by key representatives from five international cruise liners who were present to engage with representatives from the six sub-task forces to provide constructive feedback on the respective ports’ infrastructure, operations and future.

Results of these engagements were positive and remedial actions were taken by the respective sub-task forces to address the issues raised. During Cruise Shipping Asia-Pacific 2013, the largest cruise-focused convention in Asia-Pacific, which was held in Singapore in October 2013, Malaysia was singled out amongst other Asian countries by key international cruise industry representatives with high commendations on its ongoing efforts to facilitate the industry in a coordinated manner.

Smooth Sailing Ahead

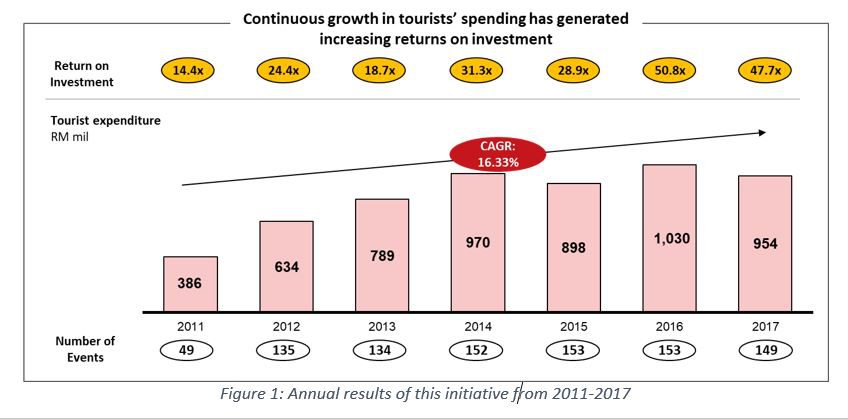

The growth of international cruise tourism in Malaysia serves as a testament to the efforts put into developing the sector since 2009. As at 2017, Malaysian ports recorded 471 international cruise calls, bringing in 924,885 passengers at primary ports in the country, an increase of 78% from 523,272 in 2013. This brought the total calls made to Malaysian ports in 2017, including local cruise ships, to 599, a 68% growth from 359 cruise calls in 2013.

These were further supported by new developments which enhanced Malaysia as a cruise destination, including the deployment of Star Cruises’ Superstar Gemini vessel East Asia and Vietnam in 2014, averaging two calls a month. In June 2016, the 4,905-passenger Royal Caribbean vessel Ovation of the Seas made its maiden calls to Penang and Port Klang. The Royal Caribbean fleet is estimated to bring to shore more than 190,000 cruise passengers to Penang, Port Klang and Langkawi for the cruise season between October 2016 and May 2017.

Moving forward, one of the industry’s key players, the TUI Group, a Germany-based travel and tourism company, is designating Langkawi as a homeport in 2018. The “TUI Discovery” will be home-porting in Langkawi starting December 2018 to cater for the winter season market.

Moving forward, one of the industry’s key players, the TUI Group, a Germany-based travel and tourism company, is designating Langkawi as a homeport in 2018. The “TUI Discovery” will be home-porting in Langkawi starting December 2018 to cater for the winter season market.

The route will cover Langkawi, Port Klang, Melaka, Singapore, Koh Samui and Laem Chabang in Thailand, Sihanoukville in Cambodia and Phi My in Vietnam. Based on the cruise schedule, there will be eight sailings with a capacity of 1,800 passengers for each sailing.

Star Cruises has also expanded its offering with multiple homeports and fly-cruise options to cater for demand from Southeast Asian tourists as well as those outside the region. This provides greater flexibility to tailor cruise routes and itineraries to suit the needs of various consumers.

To cater to the increasing demand in Langkawi, Star Cruise is expanding the berth at the Langkawi Cruise Jetty. This expansion, which is targeted for completion in early 2019, will include a wharf extension to accommodate larger cruise ships as well as a full customs, immigration and quarantine (CIQ) facility.

Additionally, now that Port Klang has been established as a Star Cruise homeport, tourists have greater ease to fly in and out of Kuala Lumpur. Furthermore, Royal Caribbean Cruises has formed a joint venture with Swettenham Port Cruise Terminal to extend its berths to accommodate larger cruise ships. The planned extension covers the lengthening of the pier from the present 400 metres to 688 metres and will cost RM151.9 million. The extension will enable the docking of two mega cruise liners simultaneously – with each carrying 4,900 passengers, an increase over the pier’s present capacity of simultaneous dockings of cruise ships carrying a maximum of 3,000 passengers.

These developments bode well for Malaysia’s cruise tourism sector and are expected to build on the regulatory and policy frameworks put in place to drive the sector’s growth, strengthening the country’s attractiveness as an international cruise destination.

It is in fact the government’s mandate that Malaysians are eager to remind the ruling administration of as it unveils its maiden annual budget. “I feel that the goverment should refocus its expenditure on the essentials, namely healthcare, education, agriculture and economic infrastructure. For the time being, the government should refrain from undertaking duplicative and non-essential initiatives.

It is in fact the government’s mandate that Malaysians are eager to remind the ruling administration of as it unveils its maiden annual budget. “I feel that the goverment should refocus its expenditure on the essentials, namely healthcare, education, agriculture and economic infrastructure. For the time being, the government should refrain from undertaking duplicative and non-essential initiatives.

Moving forward, one of the industry’s key players, the TUI Group, a Germany-based travel and tourism company, is designating Langkawi as a homeport in 2018. The “TUI Discovery” will be home-porting in Langkawi starting December 2018 to cater for the winter season market.

Moving forward, one of the industry’s key players, the TUI Group, a Germany-based travel and tourism company, is designating Langkawi as a homeport in 2018. The “TUI Discovery” will be home-porting in Langkawi starting December 2018 to cater for the winter season market.

Mindlab was initially intended to operate for a few years, but it succeeded in remaining relevant by focusing on current issues and always planning ahead of trends. Its reach across the government is unprecedented and has resulted in a major shift in how organisations think and work in Denmark.

Mindlab was initially intended to operate for a few years, but it succeeded in remaining relevant by focusing on current issues and always planning ahead of trends. Its reach across the government is unprecedented and has resulted in a major shift in how organisations think and work in Denmark. The adoption of the lab methodology globally has shown how labs help governments deep dive into specific subject areas and get their implementation programme right at the start to ensure the success of their transformation agenda. However, whilst the labs are an innovative tool and environment to chart out a true north for any transformation agenda, it is only an initial step of a transformation.

The adoption of the lab methodology globally has shown how labs help governments deep dive into specific subject areas and get their implementation programme right at the start to ensure the success of their transformation agenda. However, whilst the labs are an innovative tool and environment to chart out a true north for any transformation agenda, it is only an initial step of a transformation.